The Cat as Muse

by Shirley Rousseau Murphy

From Cats USA 2005

(A yearly magazine no longer published)

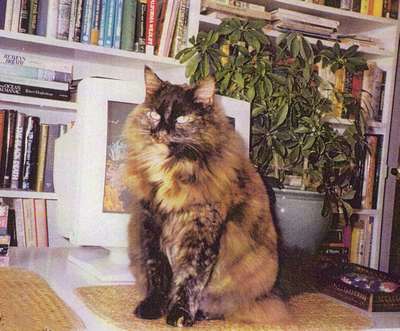

My tortoiseshell lady sits blocking the computer screen, her golden eyes narrowed with sly humor, one black-and-brown paw poised above the keyboard. E.L.T. would punch “delete” in a second if she knew which key should receive that lightning-swift strike. She has already this morning stuck her nose in my coffee and incised muddy paw prints across fresh manuscript pages. But I don't scold. She is my partner, my literary guide, my muse, as I write the joe Grey mysteries.

Most writers have a muse, some invisible presence to inspire and help shape the story: perhaps the subconscious directing the creative drive or a guiding voice that echoes from a past mentor. But if one writes about cats, only a cat muse will do--a sharp-clawed, purring critic sitting before the monitor or rubbing against your shoulder, helping to stir the creative fires.

From Ernest Hemingway’s feline muses, whose descendants today lounge in the gardens of the Hemingway Museum in Key West, Florida, to French novelist Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette’s jealous Saha and misunderstood Long-cat, the fiction of every country and every age has been enriched by the influence of the cat. Cats make up the entire cast in novels, such as “Tailchasers Song” and “Felidae,” or take a starring role as in “Thomasina.” Today, cat detectives fight crime in a half dozen contemporary murder mysteries, from my Joe Grey, P.I., to series by Carole Nelson Douglas, Lillian Braun and Rita Mae Brown.

But the cat as author's muse has no rival. By its very nature, the cat teaches its human disciple the necessary elements of a good story.

My cats instruct me in stealth and cunning, the coins of fiction. Writers, at a story’s beginning, must never tell all. They must hold back, sly in their presentation. Watch your cat. It does not leap on a gopher hole frantically digging and giving away its intentions, as would some foolish canine. The cat skillfully stays to the shadows. Only after a long, excruciating wait, does it, with one swift paw, strike a sudden, surprising blow. Just so, canny writers blend their subtle hints into the landscape of the story, withholding revelation until the final, telling scene.

And who can teach us better the contrast of emotion that is the writer’s raw material? One moment cat is a bundle of wild, clawing fierceness; the next instant it’s all loving gentleness. How cleverly it instructs us that our fictional character might lean toward pure goodness one moment, then evil in the next. Our cats’ natural contrasts teach us how to enrich our characters and shade the fictional environment.

Consider cat’s varied persona as it stares us in the eye, yowling and demanding, then slips away, slyly teasing, leading us on a hopeless chase. So must a story change mood as it feints and teases, gaining richness by its shifting views as it circles a central theme.

Within the nature of our feline muse, all possible contrasts are mirrored, magnifying human contradictions. Fear and bold attack. Shyness and brash manners. Demand for privacy and insistence on attention and love. All are conflicts essential to writers if they would sculpt real and believable characters to create a compelling work.

Although my cat muses have schooled me in the subtleties of conflict, their passion for living most keenly fires my inspiration and teaches me how to launch into story.

In the words of author and writing coach Dwight Swain, “The first real rule of successful story-writing is . . . Get excited! Hunt until you uncover something or other to which you react . . . feeling is the place every story starts . . . [The writer's] task is to bring this heart-bound feeling to the surface in your reader: to make it well and swell and surge and churn.”

Who better to demonstrate such urgency than the cat whose small being throbs with passion at every new wonder? Let the writer be as boldly driven and as joyful as his cat. My tortoiseshell muse, filled with eager, head-overpaws intensity, can’t help but instruct me. How could I not follow her?

From Stray to Queen

When E.L.T. was 8 months old, a starving stray new to our home, she discovered the joy of prowling our lakeshore. There she soon devised a new game. Stalking a dozen full grown Canadian geese, she suddenly raced at them, chasing them into the water and plowing in herself to send them flapping and honking. Standing belly deep in the water, she watched them scatter in splashing frenzy. Then she would return through the cat door, soaking wet and hugely pleased with herself: queen of the world, bold and invincible--a very different cat, then, from the frantic stray that my husband, Patrick, had found late one night at our lonely, county airport.Patrick was the only person on the dark field. He had tied down his Cessna, about to open the door of his pickup, when a demanding yowl stopped him. A thin kitten peered between the rails of the airport office porch. In the darkness Patrick could see little more than her pink mouth wide open as she shouted over the rush of wind, “I am hungry. I am cold. I am afraid. I am in great distress.”

There followed an exchange in which Patrick fed her a sandwich, arranged a box lined with his jacket, gave her a mug of water and left her, only to see her streak past him into the truck. Settling on the seat, she gave him a look of triumph. After four attempts to leave her at the airport, Patrick gave up. By the time they arrived home, he had named her E.L.T. for emergency locater transmitter, the device in a small plane that, upon impact, broadcasts a distress signal.

E.L.T. has now joined the other characters in my Joe Grey mysteries. She is Kit, a tortie of such wild enthusiasms that she seems to make her own story. I feel sometimes that I am only the typist, swiftly recording her adventures. Kit’s long, inner, monologues spring fully alive to the page, appearing as quickly as I can write.

Iinterloper as Star

The star of the series, Joe Grey, is based on a bone-thin, gray kitten that discovered our cat door and moved in, taking huge meals from our calico’s supper bowl. He lived down the street from us where he was fed on the garage floor with five large dogs. Of course he was hungry. Once he began to freeload, he gained weight and quickly took over our household. Then one morning he arrived with a broken tail, limp, dragging and infected. We nursed him through surgery, and soon he was ours. The neighbors didn’t want him back. What a jaunty young fellow he was with his eager take on life, and now with his stub tail sticking straight up like that of a small hunting dog.But it wasn’t only the neighbors who didn’t want Joe. Our calico sulked and pined until we knew we couldn’t keep Joe, that it would break her heart.

We found Joe a home with a bachelor friend and his Golden Retriever, a dog of wry humor and gentle nature. Dog and cat hit it off at once, forming an agreement of mutual advantage: On Joe’s first night in the new apartment, he knocked a bag of bagels off the top of the refrigerator and shared them with the dog. The next night Joe opened a cupboard, retrieved a box of donuts, and again dog and cat shared. When our friend married, Joe soon ruled the house of six dogs and as many cats. He remained the undeniable boss to the end of his long life, taking exactly what he wanted from the world.

If not for that bold kitten, the Joe Grey mysteries would not exist. Of course the fictional Joe Grey has a more complicated agenda and can speak, sharing his secrets with a few chosen humans. With that added ability, Joe Grey is the cops’ most reliable informant. In all other ways, he remains true to the original tomcat: same wit, same attitude. Certainly his ongoing confrontations with his human housemate are right in character.

Thus do my cats guide me in discovering and shaping a story. Together we prowl their small seaside village, running the rooftops, hunting rabbits on the wild hills or tracking a human killer. Always when I follow my characters, I experience sharply their moments of pure feline joy.

And that is the greatest lesson my cat muses teach me: To write a tale I will treasure, it must give back joy, as do my dear and complicated literary advisors.